The dream of a southern Slavic union, shattered at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, had its origin in 1172, when Stephan Nemanja of Raska overthrew Byzantine rule and united with the less-developed principality of Zeta to form the first Serbian state. Even at that time, however, the cultural influences of powerful outside neighbors served to undermine the prospects of unity among the Balkan Slavs. The Eastern Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantines became a common factor among the Serbs and their eastern neighbors, but Roman Catholicism and Hungarian culture influenced the Croats and most peoples living along the Dalmatian coast.

The dream of a southern Slavic union, shattered at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, had its origin in 1172, when Stephan Nemanja of Raska overthrew Byzantine rule and united with the less-developed principality of Zeta to form the first Serbian state. Even at that time, however, the cultural influences of powerful outside neighbors served to undermine the prospects of unity among the Balkan Slavs. The Eastern Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantines became a common factor among the Serbs and their eastern neighbors, but Roman Catholicism and Hungarian culture influenced the Croats and most peoples living along the Dalmatian coast.

The Ottoman victory at Kosovo imposed a new order over the Balkans. Serbia became a vassal state until 1459, when the Turks seized the Serbian capital of Smerderovo and extinguished what remained of Serbian autonomy. Bosnia and Herzegovina fell to the Turks in 1464, followed by northern Albania four years later. Only the tiny mountain kingdom of Zeta (later known as Montenegro) maintained a precarious independence in the centuries of Ottoman domination that followed.

In addition to the forcibly converted Janissaries, those Slavs who had resigned themselves to Turkish rule also became Muslims. Over several generations, the Islamic faith became as ingrained in the culture of thousands of Bosnians, Albanians and others as Catholicism did for the Croats and Eatsern Christianity did for the Serbs.

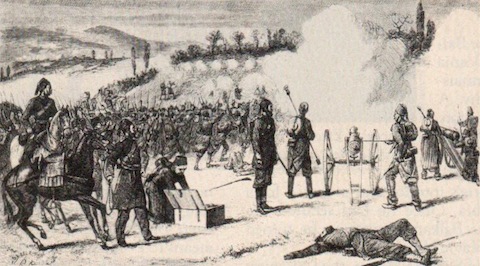

In the centuries that followed, a declining Ottoman Empire held off Austrian and Russian threats, sometimes assisted by such unlikely allies as Britain and France whenever those countries became distrustful of an excessive shift in the balance of power. Meanwhile, any of the Balkan peoples within the Ottoman sphere of influence who occasionally rebelled were subjected to brutal repression and reprisals by the Turks or the Slavic troops who served them.

In 1830, the Serbian nationalist Milos Obranovic obtained a charter from the Sultan granting self-rule — a foundation for independence upon which a succession of Turkish concessions would be added over the next 45 years. In 1875, an uprising in Herzegovina against Ottoman rule escalated into a revolt by all Balkan nations. Imperial Russia, caught up in the fervor of Pan-Slavism, came to the aid of its “little brothers”. By 1878 the Turks were defeated and Serbia’s complete independence became official once more. But the powers of western Europe, again fearing an upset in the balance of power, intervened and through the Treaty of Berlin kept Bosnia and Herzegovina under nominal Turkish rule, but with Austrian soldiers actually defending the two provinces. On October 8, 1908, Austria annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina outright. Although the outraged Serbian government was finally compelled to recognize that fait accompli on March 31, 1909, a movement of ardent Serbian nationalists called the Black Hand resorted to acts of subversion and terrorism with the utlimate aim of wrestling Bosnia-Herzegovina from Hapsburg rule and assimilating it into a united Yugo-Slav nation. Their ultimate coup occurred on June 28, 1914, when Gavrilo Princip, a 19-year-old Bosnian nationalist acting under the influence of the Black Hand, shot and killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife while they were visiting the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. The result was the unanticipated train of events that precipitated World War I. After the devastating global conflict ended on November 11, 1918, a Yugoslavian kingdom did at last emerge from the dismembered remains of the Hapsburg and Ottoman empires.

The Yugo-Slav nationalists finally got what they wanted, but their dream was destined to suffer a rude awakening. In 1934, King Alexander of Yugoslavia was assassinated by a Croat while visiting France. Centuries of social and religious differences surfaced as the Croats and Muslims accused the Serbs of dominating political and economic affairs.

In World War II, a new invader entered the Balkan arena. Wishing to come to the aid of his Italian allies bogged down in Greece, German dictator Adolph Hitler secured an alliance from the Yugoslav regent, Prince Paul, on March 25, 1941. Within 48 hours, however, a coup by anti-German Yugoslav military personnel sent Paul into exile, and his successor, 17-year-old Prince Peter, renounced the agreement. On April 6, an enraged Hitler responded with an invasion that overran the country in 11 days — largely thanks to the failure of Yugoslavia’s contentious ethnic groups to put up a united resistance. The Croats, in fact, became active allies of the Nazis, as did the Bosnian Muslims. The Croatian puppet state of Ustashe leader Ante Pavelic extended its eastern borders to the Drina River, a territory later reclaimed by present-day Croat nationalists.

The German occupation became a nightmare, mainly due to two guerilla forces. The Chetniks, led by Draza Mihailovic, were a royalist, Serbian nationalist group. The Partisan movement, led by a Croatian-born Communist named Josip Broz — later best known as Marshal Tito — embraced his vision of a unified Yugoslavia. Fearing Tito more than the Germans, Mihailovic eventually made an accomodation with the Nazis, a Devil’s bargain that would cost him dearly after the downfall of Hitler’s Third Reich on May 8, 1945. By 1946, Tito had prevailed and Mihailovic was executed as a traitor.

Ruling Yugoslavia with a combination of charisma and ruthlessness, Tito managed to hold the country together. He even impressed the anti-Communist United States in 1948 when he stood up to Russia and kept Yugoslavia outside the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact. Tito, however, proved to be an exceptional and irreplaceable statesman. Following his death on May 4, 1980, his successors tried to preserve the vestige of unity in the face of resurgent ethnic restiveness by installing a collective presidency, originally written into the Yugoslav constitution in 1974, by which a new president would be elected annually and alternately from each of the six republics or two autonomous provinces. Despite the transformation of Tito’s unified state into a virtual confederacy, trouble resumed when ethnic Albanians wishing to drive out the local Serbs demonstrated in the province of Kosovo in 1981.

The decline and fall of Eastern European Communism in 1991 was accompanied by the emergence of new independent nations, not only within the former Soviet Union but in other Eastern European countries — including Yugoslavia. In 1990, Slovenia rejected the principle of unification with the government in Belgrade. When Croatia seceded in May, 1991, its independence was recognized by its traditional friend, Ger,any, the rest of Europe, and finally by the United States.

More harmful in its consequences was the emergence of a breakaway Muslim Bosnian state on April 7, 1992, despite the fact that its landlocked territory had no economic viability, that it was surrounded by hostile neighbors, and that the country was hopelessly checkered with ethnic enclaves — 32-33 percent Serbs and 10 percent Croats against a Muslim plurality of 44 percent. The result, as a horrified world knows, was a violent war within a war. Bosnia was torn asunder in a vicious internecine conflict between Muslims and Serbs, intermittently involving outside attacks from Yugoslavia (acting on behalf of the Bosnian Serbs) and from Croatia.

![]()

By Jon Guttman

Military History

March, 1994

| Victory With Bitter Aftermath | Lingering Shadows Over the Balkans | Pariah as Patriot: Ratko Mladic |