Note: The events described in this article took place in the Tuzla, Zivinice, Ðurðevik and Visca areas of Bosnia from December, 1995, to January, 1996.

![]()

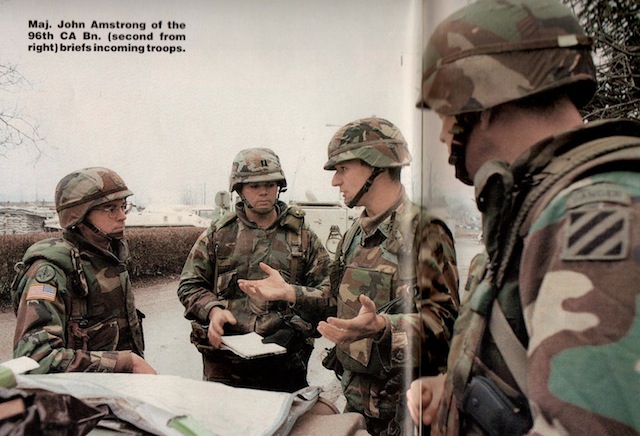

Finding suitable base areas for incoming American troops and easing the concerns of local people are fulltime tasks for civil affairs soldiers in Bosnia.

![]()

Sefket Mulavdic scowled at the Americans from behind the long, wooden table. The Bosnian had been a brigade commander in the army for 15 months before rejoining his coal-mining company, one of the largest in the country. The United Nations Protection Force had occupied pieces of his company’s land and facilities, and he was concerned about getting paid the rent due him.

The Pakistani army was on its way out and the NATO Implementation Force wanted to take over the land and facilities UNPROFOR had been using. A smooth and simple transition was needed, like one renter handing over the apartment keys to the next person.

Maj. John Armstrong of the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion from Fort Bragg, N.C., was having a hard time convincing Mulavdic he could trust IFOR. Mulavdic wondered if NATO would be more timely at paying bills than the United Nations had been. The meeting was like a game of poker, but nobody was bluffing.

“I am confident that you will see a better response time in us paying our bills,” Armstrong reassured him.

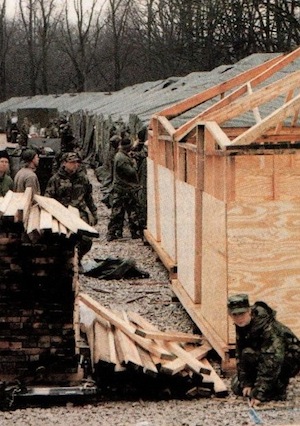

Meanwhile, armored and aviation units were camped out in pastures, and U.S. troops arrived with every flight that could cut through the fog blanketing Tuzla Air Base. They would all need some place to go, a base camp they could call home.

“Will you pay on time or no?” Mulavdic asked.

“I am not the money man,” Armstrong said. “I am the eyes and the ears for the commander looking for property. Now, about the specifics of the contract …”

The two debated back and forth about the rent and what facilities were available until a better rapport was built up on both sides of the bargaining table.

This scene was like others played out between local Bosnian landowners and a team composed of civil affairs soldiers and Corps of Engineers personnel. Their job was to find suitable land for the soldiers to occupy.

When a suitable piece of land is identified, the commander inspects it to determine if it meets the unit’s needs. Is there room to put down the number of tents needed for the soldiers? Can a flat area be cleared for aircraft? Is it just too darn muddy?

“The biggest mission for us here has been base support and establishment,” Armstrong said about the CA mission in Bosnia. “I feel like a real estate agent, showing these commanders and executive officers different pieces of property. While none of the civil affairs personnel are contract officers, we try to do our best in the negotiations.”

In researching property, CA soldiers used maps to scout out land for specific terrain features that could support a unit’s mission. For example, flat land was needed for aviation units and large open fields were essential for mechanized units.

In addition to terrain features, the tracts of land used by IFOR had to be evenly distributed among Croat, Bosnian and Serb territory, and on both sides of the zones of separation, the line separating the warring armies. After identifying the land or facility to survey, soldiers loaded up in Humvees and checked out the areas. Team sergeant SFC Dave Boling said he had traveled all over the American sector in Bosnia.

“When we came here, we realized right off the bat that there wasn’t really that much flat ground around here,” Boling said. “It’s hard to find a spot big enough to hold a good company-sized element, especially a mechanized company.”

In one land deal, the teams took several hours to locate a piece of land they thought would meet the requirements of an incoming aviation unit. When the commander inspected the terrain, it was determined the elevation was too high and the fog too thick for the helicopters.

“Air strips for rotary-wing aircraft are getting pretty hard to find,” Boling said. “We’ll find a place that’s perfect, except there’s a giant high tension power line running right through the middle of it. Anytime we find something that might be usable, we note it and get with somebody who is responsible for that area, like the mayors, and check to see who owns it.”

Bernie Rall, from the Corps of Engineers’ Phoenix, Ariz., office, is one of five realty specialists elevated to the stature of contracting officer for her duty in Bosnia. She is the one who commits the U.S. government to leasing the property. The biggest problem she faces is determining who owns what land.

“There is no formal record of real estate as you would find in the States,” she explained. The Dayton Peace Accord allows govemment-owned property to be used by the peacekeepers at no cost. “There isn’t a county courthouse you can go check with to see who owns the property. We believe most of the property is government-owned, because of the former Yugoslavia’s communist government.”

Rall said she suspected that govemment-owned land was being claimed as privately owned. The rent has escalated, in some cases, to nearly twice the amount paid by the United Nations to rent the same land.

“When it came time for us to lease the property, the prices would skyrocket. They were high to begin with. The United Nations leased these properties at high prices and, when we started looking, the prices would usually double, even triple,” she said.

“Since it’s so difficult to determine ownership, we have to take their word for it as to who actually owns the land. The only historical data we have is the price the U.N. paid for it.”

Another potential problem, Rall said, is the maintenance and reconstruction that may have to be done to make some of the areas usable.

“A lot of it is in very poor condition and hasn’t been used in a long time,” Rall said. “We don’t want to rebuild their buildings for them, but we may wind up doing that just so we have places to house the troops.”

The 60,000 members of IFOR will obviously have some kind of impact on the land and the economy during NATO’s one-year stay. Long-range planning must be considered with each contractual decision, Boling said. If a cornfield is used as a unit bivouac, for example, some improvements would have to be made before troops can use the land. After the forces have been sent home, the cornfield would have to be returned to its former condition.

“That field may supply 40 percent of that region’s corn. Even if we occupy it for only one year, the repercussions of us bringing gravel in could cause them to not have a crop for three or four years,” Boling said.

In some cases, improvements may be made to an area, but only when these improvements benefit IFOR’s mission, Boling said. Road improvements will probably have to be made for the many tanks and other armored vehicles moving through Bosnia.

“These vehicles have a tendency to tear up the road,” Boling said. “The brigade will release engineer assets to improve the roads, because the improvements also assist the brigade.”

The Military-Civilian Relations unit, made up of soldiers from Fort Bragg’s 4th Psychological Operations Group, helps prepare Bosnian neighborhoods for the arrival of several thousand American soldiers. The key to a community accepting this influx is information, said team leader SSgt. Darren Bessingpas. This is done by distributing newspapers printed in Serbo-Croatian, handing out flyers and meeting with local community leaders. The MCR unit is also capable of providing information through both radio and television broadcasts.

“We’re not here trying to brainwash the people; we’re here to inform them,” Bessingpas said. “The more the people in our sector are informed of what’s going on around them, the more cooperative they will be. Hopefully, their morale is also going to get better.”

Information can be a trade-off for both Bosnians and the soldiers. For example, to find out the locations of mines, the MCR may sponsor a mine-awareness program. Farmers who have worked the area for the last four years usually know where these dangers lie. Forming a mutual relationship of assistance is essential.

“The biggest thing we try to get across is cooperation,” Bessingpas said. … We’ll give you information about what we’re doing. Try not to interfere with our operations.”

The work of finding land and facilities for the soldiers continues as base camps are established throughout Bosnia. Additionally, contracts were awarded for such services as laundry, maintenance, and fresh bread, Armstrong said. This work must also be divided so as not to have an adverse impact on the community.

“We wouldn’t want to go to just one baker,” Armstrong explained. “If his production for one day is 1,000 loaves of bread, we wouldn’t want to hire him and take 999 loaves from him. That would leave one loaf of bread for his normal customers. So we will identify many bakers and try to spread the profits, while trying to impact as minimally as possible on the civilian population.”

Spreading the wealth is important if IFOR is to maintain its neutrality and have an even impact on the economy of Serbs, Croats and Bosnians. To hire too many bakers from one group would appear preferential.

The second phase of the CA mission in Bosnia will be to establish civil-military operations information centers, sites for liaison between the forces and the civilian population. For example, if a farmer’s field is destroyed in a maneuver accident, a claim may be filed at the information center. The third phase of the CA mission will be to assist displaced persons and aid community relations projects like soldiers visiting hospitals.

“There may be friction because an armored unit moves into their neighborhood, but we’re going to try to reduce that friction,” Armstrong said. “We will help to create conditions of peace. As the conditions get better, people will be less likely to want to fight.”

![]()

Story and Photos by SFC Larry Lane

Soldiers

May, 1996

| 432nd may be home from Bosnia early | Managing Civil Affairs in Bosnia | On the Gate in Tuzla |